I have argued before that, in order to create something truly creepy, you can’t be afraid of it being a little silly. Junji Ito understands this, and so does Koji Shiraishi.

Recently, I had the great pleasure of introducing a packed house at the Stray Cat Film Center to Shiraishi’s 2005 classic Noroi, which is probably my favorite horror film of the 21st century so far. In so doing, I learned that a lot of people who don’t have my very specific predilections are largely unaware of Shiraishi. This makes sense, as a plurality of his more than one hundred films have never received any kind of official English-language distribution.

Noroi (which spent some time on Shudder before being released stateside as part of Arrow’s J-Horror Rising boxed set) was my first introduction to Shiraishi. Back then, though, you couldn’t watch it on Shudder, or anyplace else reputable. You had to track down fan-subbed rips on YouTube or wherever you could manage.

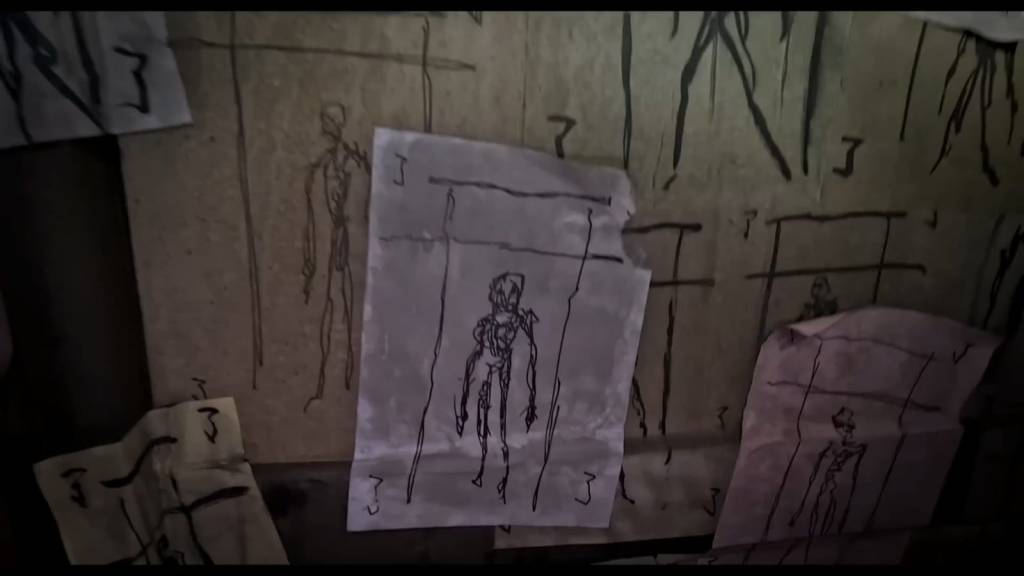

Seeing Noroi under those conditions rewired my brain. Here was not only the best and most convincing found footage (more accurately faux documentary) movie I had ever seen, here was also perhaps the best expression yet mustered of Lovecraft’s “piecing together of dissociated knowledge [to] open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and our frightful position therein…”

From there, I went down a rabbit hole that would have made Noroi protagonist Kobayashi proud, chasing Shiraishi and, in particular, his found footage-adjacent movies. From Noroi to Occult (2009), from Occult to Cult (2013), with a stop-off along the way for Shirome (2010), in which Shiraishi plays himself, taking real-life idol group Momoiro Clover Z through a haunted house.

While Shiraishi may understand the found footage format better than perhaps any filmmaker who has ever experimented with it, however, it makes up only a portion of his filmography. I also followed Shiraishi into more straightforward films: Carved: The Slit-Mouthed Woman from 2007 (also in Arrow’s J-Horror Rising set); Sadako vs. Kayako in 2016; even House of Sayuri from just last year.

Along the way, he has also continued to experiment with different strains of found footage. Among Shiraishi die-hards, one of his most popular undertakings is the long-running Senritsu Kaiki File Kowasugi series, which has something like nine installments. Beginning as found footage horror in the same vein as some of the others I’ve mentioned, Senritsu Kaiki File Kowasugi is ambitious and definitely not afraid to get silly before all is said and done.

To some extent, that is the push and pull of a lot of Shiraishi’s films. While Occult is a classic that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Noroi, many of the others cross that line into becoming a little too silly – at least, for what I want them to be. Which is to say that, while I have enjoyed my time with virtually every Shiraishi film I’ve ever watched, there has never been another Noroi or Occult… possibly until now.

When I first started hearing about Kinki, I got excited, and not just because early buzz was calling it Shiraishi’s most Noroi-like thing since that film. The premise (a writer for a magazine about occult phenomena who goes missing while researching his latest story) sounded almost like a direct lift of Noroi’s premise, and the trailer promised more straightforward creep than much of the found footage work that Shiraishi had been doing in recent years.

Though it lasted only a relatively short time, the wait until I could see a subtitled version of Kinki felt interminable. Finally, though, it arrived. So, was Kinki the next Noroi?

No, of course not. It couldn’t possibly have been, because when I saw Noroi, I had no idea what I was getting into. I had never experienced anything like this. I had no expectations, beyond a movie that I had heard was weird and great. With Kinki, I was hoping for Noroi, so there was no way I could possibly get it.

But it came pretty damn close.

Shortly before showing Noroi at the Stray Cat, I finally tracked down Ura Horror, an anthology of short found footage vignettes Shiraishi released in 2008. At the time, I described Ura Horror as like watching Shiraishi’s sketchbook. If that’s the case, then Kinki is often like watching him playing his greatest hits – some of the elements first deployed in Ura Horror even make comebacks here.

What’s wild about how much Kinki feels like a Shiraishi “best of” compilation is that it isn’t actually a Shiraishi original. It is, instead, adapted from a book, originally published serially online, by an author known as Sesuji who “has recently burst into the Japanese horror scene like a world ending comet.”

That quote is from Baxter Burchill, who knows a lot more about this than I do. I’ll let them take it from here, from their own review of Kinki, which was one of the ones that made me realize I had to see it:

Utilizing a found footage style but supplanted to prose, Sesuji writes much of their work (Kinki included) from the perspective of articles and interviews, transcripts of audio files and TV programs. They take an epistolary form – a through-line narrative emerging through the reoccurring writing of the journalist protagonist – and mutate it into an almost mind-bogglingly expansive vision of the modern world and how we interact with it. It’s a story and a style that revels in the ambiguity of media, in the blurring of reality in the face of how we present it. And then within that addictive push and pull of mystery and answer, they create horrifying eldritch suggestions, whispering in the corners of a broader mythology of spirits and the occult that makes one thing perfectly clear: no matter how much we might see in a video, it’ll never even come close to the truth.

Sesuji feels, in other words, like the world’s most perfect, natural fit collaborator for Shiraishi.

The book, About a Place in the Kinki Region, is getting an English-language release early next year. I’ve already pre-ordered, and I’m looking forward to reading it when it comes in; to seeing how the experience of the book and movie mirror each other, and how they differ. You can expect more about it here, when that happens.

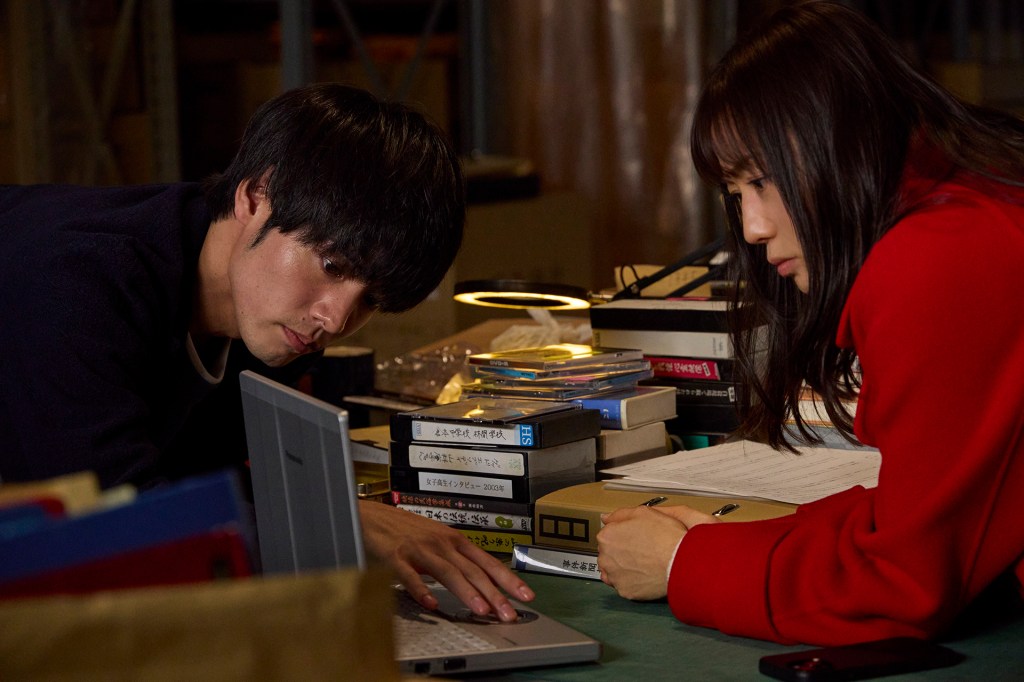

Back to the movie, though: Unlike Noroi, Kinki is not entirely found footage (or faux documentary). It combines clips of found footage, news broadcasts, TV shows, and so on with traditional third-person filmmaking. The result is something that looks more polished than many of Shiraishi’s found footage experiments, and feels less immediate.

Baxter is convinced that the change in approach does something else, too, though, and I don’t know that I disagree. “By partially pulling out of the fake documentary world and grounding itself within a more distanced perspective, Kinki has become the Shiraishi film most directly concerned with physical form of media itself, with video and text as objects beyond their contents.”

This begins a sea change in the closing legs of the picture, as the two formats start to break down. When our would-be occult investigators leave the archival room where they have spent much of the movie to try to track down the secrets of the unfolding web of connections themselves, they naturally film their attempts, and the cinematic style, which has heretofore kept the two formats distinct, begins to switch effortlessly between “found footage” shots and more “objective” sequences, often in rapid fire.

There are ruminations to be made here. About memory, and our relationship with media, and how we use media to, well, mediate our own experiences. As with the best of Shiraishi’s work, however, these ruminations stay in the background. First and foremost, Kinki is about telling a creepy story. What that story means takes a deserved back seat.

At the time that I write this, I have watched Kinki only once. By comparison, I have lost track of how many times I’ve watched Noroi – at least six, just in the past couple of years. And maybe the best thing I can say about Kinki, for those who are hoping to find in it the next Noroi, is that I already want to watch it again, even though I just watched it last night.

With just this one viewing under my belt, I don’t think it does what Noroi does. There, everything feels real, every puzzle piece fits unerringly into place. The sensation that you are watching a story being revealed by the gradual “piecing together of dissociated knowledge” is absolute, inescapable.

The narrative of Kinki doesn’t fit together quite as perfectly – at least, not at first glance. (It probably doesn’t help that the subtitles I had access to don’t translate text, and there is… a lot of text.)

Take, for example, the stone that shows up near the end of Kinki and suddenly occupies a place of prominence in several of the otherwise disassociated storylines. One could make a comparison between that stone and the story of Kagutaba in Noroi, but when Kagutaba first shows up partway through that film, it fills completely a void that had previously existed in each unrelated narrative. Not so much here.

Nonetheless, while the solution of Kinki may leave more questions than it answers, it is no less satisfying for all that, and it features some imagery that is Shiraishi sampling from some of the wildest of his Senritsu Kaiki File Kowasugi instincts (and maybe a little of Hayao Miyazaki), without ever letting them not be scary. I think there will be a lot to discuss about the ending of this film once more of us have gotten a chance to see it.

And maybe that messier lore is intentional. I’ll go back for a moment to Baxter’s description of Sesuji: “no matter how much we might see in a video, it’ll never even come close to the truth.” Maybe that’s what Kinki is reaching for, with its tangled mythos. Does it get there? I think I’ll need more viewings to say for sure.

But it gets close. And that’s not nothing.

Leave a comment