-

Continue reading →: “We have uncovered history, gentlemen.” – Green Hell (1940)

Continue reading →: “We have uncovered history, gentlemen.” – Green Hell (1940)What has to have been more than twenty years ago now, I saw a promotional still of the incredible “sun temple” set from Green Hell, and knew that I had to watch it. Of course, it was more than just the set. Green Hell is the second-to-last movie directed by…

-

Continue reading →: A Nightmare Four Years in the Making

Continue reading →: A Nightmare Four Years in the MakingAs I mentioned last time, I regularly co-host a live podcast and free screening series at the Stray Cat Film Center here in KC. Next month will mark four years of the Horror Pod Class being at Stray Cat, so I thought it would be fun to crunch a few…

-

Continue reading →: Year of Monsters

Continue reading →: Year of MonstersThose who aren’t in the Kansas City area may not be aware that I co-host a monthly live podcast at the Stray Cat Film Center. The story of how I came to succumb to the curse of being a middle aged white guy and therefore co-hosting a podcast is a…

-

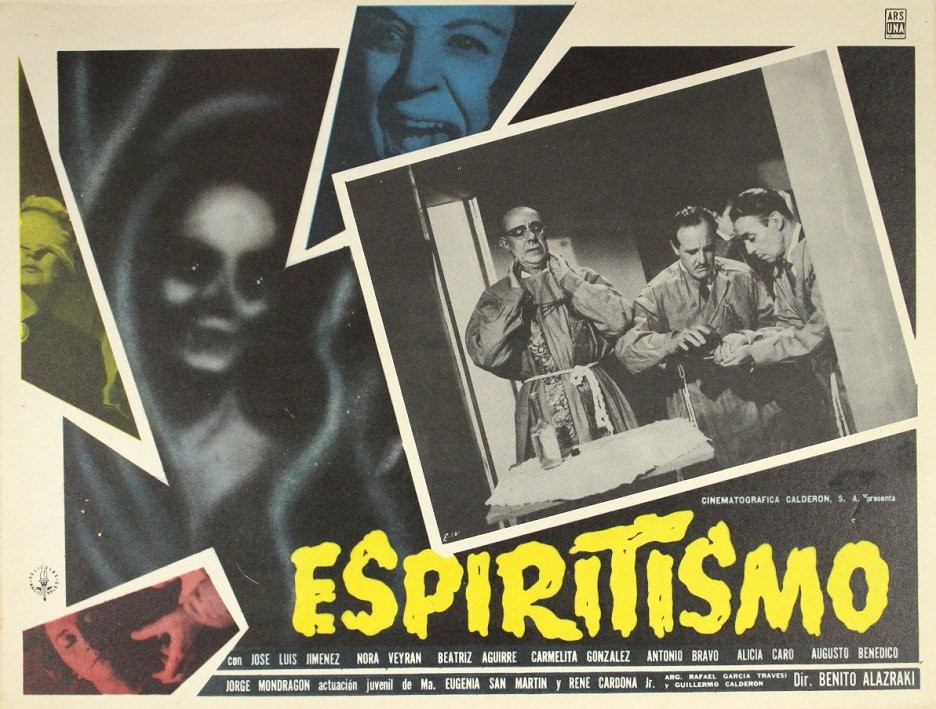

Continue reading →: “Horrifying things, inconceivable to the human mind.” – Spiritism (1962)

Continue reading →: “Horrifying things, inconceivable to the human mind.” – Spiritism (1962)Recently, I stumbled upon a library of K. Gordon Murray releases on the Internet Archive. (Which would have been worth it for this thing alone.) Given my predilections, I knew what I had found immediately, but for those who have spent their lives in more worthwhile pursuits than I, who…

-

Continue reading →: This Is the End (of the Year)

Continue reading →: This Is the End (of the Year)For a recent freelance assignment, I did some research on why the new year falls when it does (at least, for those of us who mostly use the Gregorian calendar). The answer is complicated and, as with the answer to most questions, boils down to, “There are several compelling theories,…

-

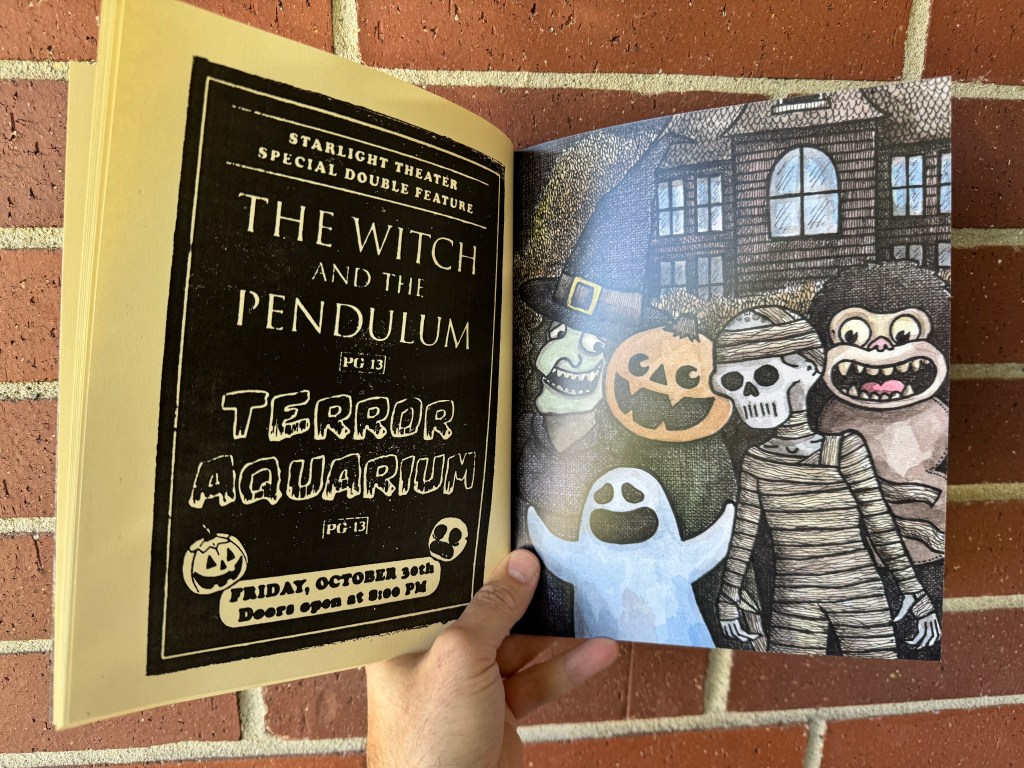

Continue reading →: Best Horror

Continue reading →: Best HorrorI didn’t publish a lot of new stories in 2025, but I had fun with the ones I did, including the two (and a half) stories in the Starlight Theater Halloween Double-feature zine that I did with artist Patric Bates, and my story “The Phantom of the Wax Museum” in…

-

Continue reading →: “Thank you for watching.” – Kinki (2025)

Continue reading →: “Thank you for watching.” – Kinki (2025)I have argued before that, in order to create something truly creepy, you can’t be afraid of it being a little silly. Junji Ito understands this, and so does Koji Shiraishi. Recently, I had the great pleasure of introducing a packed house at the Stray Cat Film Center to Shiraishi’s…

-

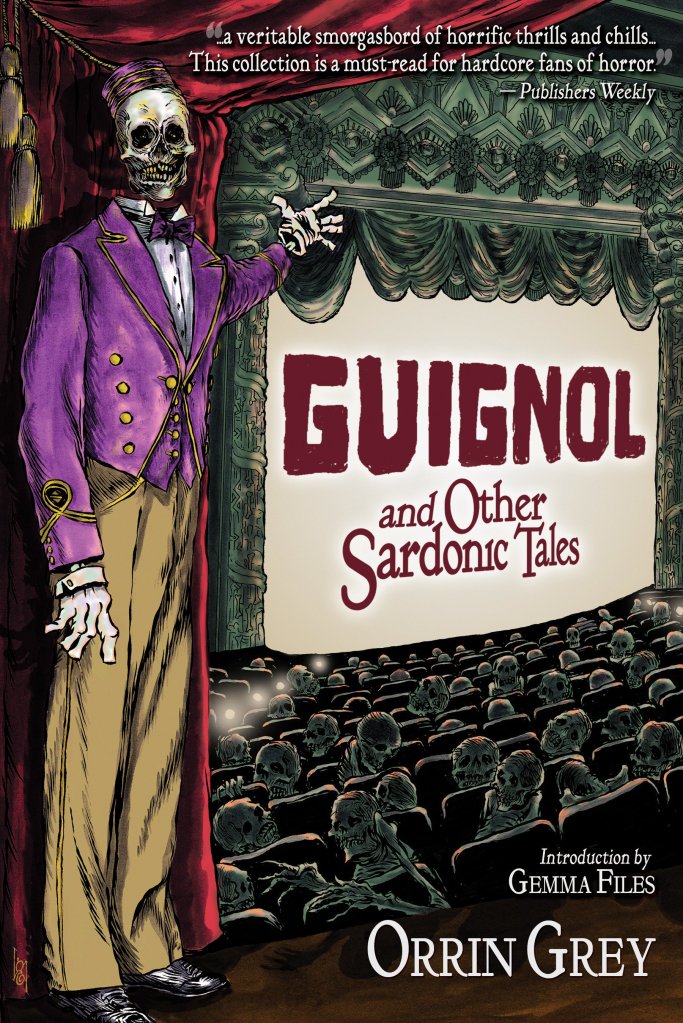

Continue reading →: Kind Words

Continue reading →: Kind Words“On the level of Matheson, Grey is one of the best living short fiction writers of our time.” That quote, from a recent Goodreads review of my 2022 collection How to See Ghosts & Other Figments, obviously made me very happy – especially as I think How to See Ghosts…

-

Continue reading →: We’ll Send Him Spooky Movies

Continue reading →: We’ll Send Him Spooky MoviesIf you’re like me, and I know I am, you spend an inordinate amount of your time watching old episodes of Mystery Science Theater 3000. Specifically, for me, Joel, Mike, and the ‘Bots have become a part of my nightly bedtime ritual. Which means that I’ve watched many of the…

-

Continue reading →: Two Came for Halloween

Continue reading →: Two Came for HalloweenFor those who haven’t been following along, I have not one but two books that came out this month, both of which are currently available – one of them for a very limited time! It all started when Patric Bates, an artist whose work I really love, posted a painting…

Orrin Grey

Rondo Award-nominated author Orrin Grey writes disjointed and irresponsible things about monsters, ghosts, and sometimes the ghosts of monsters.

Reach me in the beyond…

Strange Transmissions

Do you dare to sign up for eerie updates from the other side?

This site is part of The Wood-Paneled Web Ring.

← Previous • Random • Next →

What is this?